Hang on, you’re probably saying; you mean the ancient Egyptians – the same Egyptians who built pyramids and temples, quarried tombs in the Valley of the Kings and filled them with treasure, organised the massive machine of state and sent armies marching and conquering all over the Near East, those Egyptians – thought the best possible way they could represent in writing the King they believed was a god on earth, was: a blade of grass and a loaf of bread? Are you sure we’re talking about the same Egyptians? And anyway, the Mesopotamians invented writing first.

Well, I could conduct a forensic investigation into the etymology of the Egyptian word for King, but I think you’d doze off long before the end. You’d wake up to a dark office (especially if you’ve got motion sensors on your lights), the baleful glare of the screen saver and the symphony of banging sounds that denotes the arrival of the cleaners. So I’ll try to make it a bit more interesting by bringing out the narrative.

Once upon a time, in a land far, far away (unless you’re reading this in Egypt, in which case it’s pretty close), some forty-odd independent tribes occupied the valley and the delta of the river Nile. We’re talking about a time way before the invention of writing. For at least one of the valley tribes, the sedge plant assumed great significance. It’s a useful plant (papyrus is a member of the sedge family, and you can make lots of things with it besides writing materials) and it also has a symbolic significance, as the green shoots sprouting through the mud in the ancient springtime came to represent the rebirth and regeneration part of the cycle of life and death.

For these and who knows what other reasons, the sedge plant became a heraldic emblem among the tribes in the Nile valley. All the tribal leaders had different emblems, although some of them were out of the same design stable. Anyway, as tribes will, they went to war. Over many years, through a process of conquest and assimilation, two leaders managed to unite the Nile Valley and the Nile Delta tribal lands respectively into two kingdoms: Upper Egypt or the Nile Valley, and Lower Egypt, or the Nile Delta.

The King who united Upper Egypt used the sedge plant as his emblem and was strongly identified with it; so much so, that he was known as “He of the Sedge”. The Egyptian word for sedge is swt (pronounced sut to rhyme with loot) and “He of the Sedge” is ny swt.

The inevitable battle for supremacy over the whole of Egypt took place somewhere around 3000 BC, and of the rival Kings, He of the Sedge won. So the title which had once meant only “King of Upper Egypt”, although it continued to be used as such, also came to be used simply as one of the words for King. Over time, the letter t became silent and the word evolved into nsw / nesu.

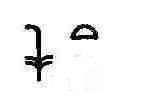

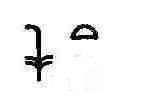

Remember when I said a few posts back that the principle of Egyptian writing was to use pictures to represent sounds? When they wanted to write the sound sw / su, they drew a little picture of the sedge plant, because that was how its name sounded:

They had another symbol they used to write the letter t : the word for bread was t / te, so they used the loaf sign to represent the t which once existed in the word swt but fell out of use:

Stop there a minute, you’re probably saying; I’m looking at the word for King.:

Nsw, right? So what happened to the ny? Ny obviousy means “He of”. Where is it? We’ve got a sw all present and correct, a t that’s superfluous to requirements and a completely missing ny.

Well spotted. This is a very abbreviated spelling of the word nesu, pared down to its basic heraldic element, the sedge sign. This is the kind of thing that happens with formulae. You want to write them quickly because you have to write them so frequently, so you strip them down. You’ll appreciate that when you’re scribbling on that card, especially if your office has clustered birthdays / lots of women of childbearing age / a high turnover of staff / all of the above.

However, paring it down to one tall, thin letter would leave an unpleasing gap above the short, wide sign which comes next, so they filled it with the superfluous t. Whatever you may think of their flexible approach to writing, they allowed nothing to compromise their artistic integrity.

If you look at the longer spellings of nsw, you’ll see the missing n: it’s the wiggly line:

We’ll come to the letter n later in the formula. Don’t worry, it’s there. In fact, it’s got a whole word to itself.

Oh, and about the Mesopotamians – shh, don’t tell the nsw. You never know what a powerful sign like that might do.

It does look as though there’s the beginning of some kind of addition to the circle (if it is a circle) on the right hand side.

It does look as though there’s the beginning of some kind of addition to the circle (if it is a circle) on the right hand side. ![]() then the scribe may have put it in because he was thinking of a similar word, seshu, meaning ring, and put the ring hieroglyph in as well.

then the scribe may have put it in because he was thinking of a similar word, seshu, meaning ring, and put the ring hieroglyph in as well.

netjer, god, is written with the flagstaff hieroglyph which you’ll remember from before, plus the seated god determinative we saw earlier in this inscription.

netjer, god, is written with the flagstaff hieroglyph which you’ll remember from before, plus the seated god determinative we saw earlier in this inscription.