You’ve heard them singing carols in the office. You’ve heard them karaoke down the pub. This is the best time of year to decide which of your colleagues merits the last phrase of the offering formula:

maa-kheru; true of voice.

We’ve had kheru, voice, before. It was in the complex little group of signs which make up the standard phrase for “an invocation offering of bread and beer”:

where “invocation” is literally “that which comes forth by the voice”. And there’s kheru, right in the middle of the group, like a wooden spoon ready for stirring the pudding (which would make the other signs a chopping board, a bag of flour and a bottle of brandy in seasonal montage straight out of the Lakeland kitchenware catalogue. Except they’re not.) But you know it’s an oar, and the other signs are a house, a loaf of bread (naturally) a jug of beer and the invisible owl.

So now we have the oar again, twice in one formula. They did like sticking their oar in, the ancient Egyptians. But what’s the first sign,

maa? A doorstop? An eraser? Nothing so mundane. The wedge-shaped sign maa (very easy to draw) represents a platform or pedestal, as here supporting a figure of the god Ptah (from Tutankhamun’s tomb furniture):

(Ok, you could use him as a door wedge, I’ll give you that. But he would be far from mundane. There could be a whole interior design industry in this for someone – and that someone will need an office, and that office will need hieroglyphs…. I must stop getting carried away.)

Back to maa – the pedestal has that distinctive shape because it in turn is a representation of nothing less than the primeval mound; the first bit of land to appear from out of the waters of chaos at the very creation of the world. The Egyptians were used to seeing mounds of land rise from the water every year, as the floodwaters of the Nile receded after the annual inundation, leaving behind fertile silt which they could cultivate. (So, we have to assume that Ptah is standing on a little island, with the waters of the primeval ocean lapping almost at his feet, at the bottom of the little slipway on his pedestal.) The Egyptians assumed that this was how the gods had first created the land on which they lived. To them, this pristine terra firma meant the world the way the gods had created it, the way the world was meant to be. Maa meant “true” or “right” or “just” in the sense of “the proper order of things”.

Here is an example of the maa kheru group in a carved relief:

True of voice: the “of” is unwritten but understood from the construction. The maa hieroglyph is easy to draw: a thin rectangle with one slanting short side.

True of voice: the “of” is unwritten but understood from the construction. The maa hieroglyph is easy to draw: a thin rectangle with one slanting short side.

But if our tomb owner Senusret was “true of voice”, what did that mean? They didn’t have karaoke in the netherworld, did they? No. It was much worse than that. To get into the Egyptian afterlife, you had to win the divine version of the X Factor.

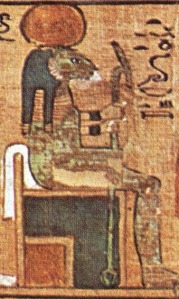

Anyone who thinks the X Factor is hell on earth will get the idea of the Egyptian afterlife. If life on earth was Round 1, to go forward to the afterlife or Round 2, you had to impress a panel of judges. Here’s a scene from the show:

On the left,we have the tomb owner being led onstage by his divine sponsor, the god Anubis. In the middle, the scene shows an early version of the machine used to record the audience’s verdict. Back then, in the days before electronic voting buttons, they used a weighing scale. In the right-hand pan of the scale is a feather, representing truth, order, justice and all those primeval virtues. In the left is the tomb owner’s heart.

On the right of the scene, in their own special booth, sit the judges: Osiris, the Simon Cowell of the underworld, sits on his throne, backed by two divas of the day, the goddesses Isis and Nephthys then, and fronted by four lesser judges, his own four sons, who stand on a lotus blossom.

The format of the show is this: to qualify for the next round of existence, the tomb owner has to declare that he has led a good life on earth. But just saying so is not enough; he has to prove it. To test whether or not he is speaking the truth, the gods weigh his heart against the feather. If his heart is not weighed down by sin and falsehood, it will balance the feather and he will be let through to the next round. If it is heavier than the feather, it will be thrown to the crocodile-headed she-monster waiting by the weighing scale, (her name is Devourer-of-Hearts, but let’s call her Anne) and the tomb owner will be thrown off the programme – you are the weakest link, goodbye. That won’t happen, though, because in the finest traditions of audience voting reality TV, Anubis is rigging the result by fixing the scale. The Ibis-headed god Thoth is standing by like the Lottery adjudicator to verify the outcome. And sure enough, Anubis is conducting the tomb owner, who has been proven to be speaking the truth, to Simon, sorry, Osiris, who declares him fit to go forward to the final.

And ever after, our tomb owner is known as “true of voice”, as a sign that he has passed the test and successfully entered the next world.

So there we are: at the end of the offering formula. You know it all now:

Hetep di nesu Usir neb Djedu, netjer aa, neb Abju, di ef peret-kheru (em) te henqet, kau apedu, shes menkhet, khet nebet nefret ankhet netjer im, en ka en imakhy Senusret, maa-kheru.

Hetep di nesu Usir neb Djedu, netjer aa, neb Abju, di ef peret-kheru (em) te henqet, kau apedu, shes menkhet, khet nebet nefret ankhet netjer im, en ka en imakhy Senusret, maa-kheru.

“An offering which the King gives (to) Osiris Lord of Busiris, the great god, Lord of Abydos, that he may give invocation-offerings (consisting of) bread, and beer, meat and fowl, alabaster and clothing, and all good and pure things by which a god lives, to the ka of the Revered One, Senusret, True of Voice.”

How’s that for a Christmas list?

![]()

![]() , khenty Khem, Foremost (of) Letopolis.

, khenty Khem, Foremost (of) Letopolis.![]() The middle and lowest of them will be familiar to old Office Hieroglyphs hands, but the top one is new to this blog:

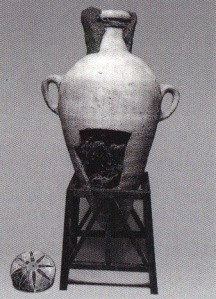

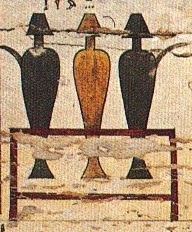

The middle and lowest of them will be familiar to old Office Hieroglyphs hands, but the top one is new to this blog: ![]() , a row of water jars on a stand making the triliteral sound khent. (Ignore the diagonal line cutting across the top left hand corner of the sign in this example, it shouldn’t be there.) The wavy ripple of water beneath reinforces the n sound, and that perennial favourite, the loaf of bread, reinforces the t. The y sound is not spelled out here; it’s just understood. Khent = before or in front of, khenty = the on who is in front or foremost. It was obvious to the Egyptians from the context that khenty was what was meant here, and adding in the y would have spoiled the arrangement of the signs, so they left it out.

, a row of water jars on a stand making the triliteral sound khent. (Ignore the diagonal line cutting across the top left hand corner of the sign in this example, it shouldn’t be there.) The wavy ripple of water beneath reinforces the n sound, and that perennial favourite, the loaf of bread, reinforces the t. The y sound is not spelled out here; it’s just understood. Khent = before or in front of, khenty = the on who is in front or foremost. It was obvious to the Egyptians from the context that khenty was what was meant here, and adding in the y would have spoiled the arrangement of the signs, so they left it out.