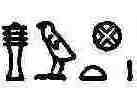

Let’s look at the nameplate attached to the portrait of the third MD of the divine family firm. Here it is:

Reading right to left, from the top of the column to the bottom, it says:

Gb `it ntrw Geb it netjeru Geb, Father of the Gods

The first hieroglyph is clearly a bird, and although it’s cursively rendered, there’s something familiar about its face. What do you mean, you don’t see it? Have a look at this one:

Recognise him now? I’ll give you a clue: last time we met him, it was as a disembodied head. Ah – got it! Yes, that’s right, his head had made a sola appearance in Office Hieroglyphs as 3pdw, apedu, fowl, in the list of offerings. Now we have the whole goose – a white-fronted goose in fact, just like this one:

Beautiful, isn’t he? He’s tricky to draw, but worth it. I usually start with a short horizontal line for his beak, curve up and over for his head, come inwards for his neck and then sweep outwards and downwards for his back, down to the tip of his tail. The you can return to the base of his beak, draw a flattish line for his chin and swoop in and out again for his neck and breast, pulling the line downwards for his belly and joining up the two lines at the tail tip. Make a deep curve across his body for the wing, and make the wing tip cut the line of his back. Then you can put in two short lines of his legs and a baseline for his feet. A final dot for his eye, and he’s done.

The goose hieroglyph is a biliteral, gb. The foot hieroglyph which represents the letter b is another old Office Hieroglyphs friend, and is only there to reinforce the b sound already contained in the goose symbol. Finally, the seated god hieroglyph, familiar from many of our divine corporation nameplates, denotes that this is the name of a god.

The next group looks straightforward, but, like Geb, it’s a treacherous item: ![]()

You’ll recognise the top half of Tefnut’s snake sandwich; the loaf of bread and the horned viper. On the face of things, this group should be pronounced tef, but in fact it’s the word ‘it, it, father. Other versions of the word have the inital ‘i written out in full, but ‘i is a semi-vowel (a vowel with some of the force of a consonant) and we know the Egyptians placed greater emphasis on writing down the consonants than on writing vowels, so they often left out the ‘i of ‘it. The viper in this case is not the letter f but a determinative – a soundless symbol put in to show what kind of word this is – whose significance is obscure.

And so to the final group of hieroglyphs in Geb’s title:

We’ve seen them all before: the temple flagpole representing the sound ntr, the seated god determinative; the loaf of bread for the letter t and the three short strokes denoting the plural ending w, the whole lot reading ntrw, netjeru, gods. Strictly speaking, the letter t shouldn’t be there. As we know, it’s a feminine ending, which might suggest that Geb is claiming only to be the father of the goddesses, which would not do him justice. We know he was not exactly a champion of female rights, so we can’t take this as evidence of positive discrimination in the workplace. I think it’s probably crept in there because the similar title God’s Father, found in the titles of certain high-ranking Egyptian nobles and possibly meaning King’s Father-in Law, was often written with the flagpole sign followed by the loaf of bread from ‘it, father, and the scribe just kept on going because he was so used to writing that title, even though he’d already written the word for father.

But enough of these bureaucratic technicalities. Geb was the third patriarch in the family firm. Why did he claim to be the father of the gods? What was so special about his divine kids? Well, let’s meet the gods’ mother, first, and after that we’ll find out.